Everything I Did Was For You

More than anything, I remember how oppressive the hospital felt.

Many of the specifics are lost to time, to the caverns the subconscious creates to protect our most fragile selves, but the stale air, the haunting white walls, and the dour lighting never spoke “healing” to me. It felt like what it very often is: the place people go to die. And at 11:36 AM on November 13th, 2016, my father did die. He had been in a coma since the 10th, the day his car was hit by a transport truck during his commute to work. His 43rd birthday was on the 11th.

I remember holding his hand on one of those days at the hospital, and saying to him that his life wasn’t over. That he still had things to accomplish before he went. I lied to my father, not for his sake but for mine, to reassure myself that this traumatic event that had already happened could still be reversed. It didn’t take long for the hollowness of the gesture to reveal itself, or for the downpour of condolences and platitudes to wash over me. As horrifying as the experience was, for as much grieving as I had ahead of me, the world moves on. We are the ones who don’t.

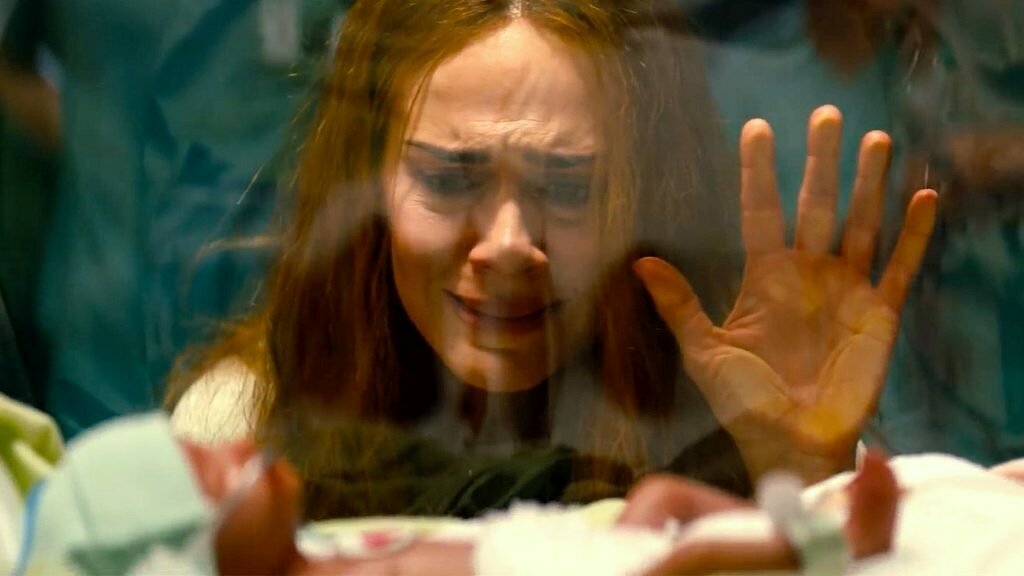

At the beginning of Run, we are introduced to Diane Sherman (Sarah Paulson) in a hospital. She has just given birth, and she looks over her newborn baby, clearly unwell and barely clinging to life, and asks: “Will she be okay?” The lineup of faceless doctors behind her give their answer by saying nothing. Fielding such questions and all the emotions associated with the immediate aftermath of personal tragedy are a regular fixture of their work. For medical professionals, encountering death is routine. They’re paid to do it. No single death can matter too much when there are other patients to attend to, but for the loved ones of the deceased, this may very well be the darkest hour of their entire lives.

It is for Diane. It was for me. And it was for my mother.

After the prologue, we fast forward seventeen years and are introduced to our main character, Diane’s daughter Chloe (Kiera Allen), who eagerly anticipates college acceptance letters that never seem to come in mail that her mother always seems to intercept. Diane promises Chloe she will “deliver it straight to you” in regards to any such letters, the first and least harmful of numerous lies she tells Chloe over the course of the film. Chloe is undeterred by her mother’s assurances, a handful of brief scenes of domestic agreeability between the two quickly giving way to deep-rooted suspicions and simmering tensions.

The form this conflict takes is familiar: a “trapped in the house” thriller, but one that mostly replaces threats of physical violence with emotional manipulation and Munchausen by proxy. It’s important to note that Diane doesn’t need to threaten Chloe to keep her contained, because Chloe is disabled and uses a wheelchair, insinuating a level of physical dependence on Diane in direct opposition of her desire to get away from her. Chloe comes to see through Diane’s lies early on, with the rest of the runtime taken up by Chloe enacting her own schemes to learn vital information and facilitate her escape. The proceedings have an airport paperback feel, with Aneesh Chaganty’s fine-tuned direction making it an enjoyable ride on a surface level. However, the movie has stuck with me in a way many recent releases didn’t, for one particular reason.

This movie understands me.

I finished my Master’s degree only a couple months before my father’s death. I had not elected to continue onward to a PhD, uncertain if I was willing to commit to several more years of schooling and the kind of financial debt I had been lucky enough to avoid due to my father planning for my post-secondary education from the time I was born. Because of his forward thinking, I was in a position to pursue my creative interests with relative security, and my mother was on her way to early retirement. For a few short weeks, there was a solid direction for both of us. Our future and our family were both derailed with one fateful incident.

Many of the events of the first year after that are vague in my memory, warped by grief and time starting to feel more like a gelatinous mass rather than properly divided into twelve month periods. It was hard to take stock of how my relationship with my mother changed in the moment because the deterioration was so gradual, marked less by visible signposts of change than by a decay as shapeless in my mind as the time it was happening in. I don’t remember what the first and least harmful of the lies was. It was probably something so inconsequential that I would never have noticed. All that mattered is that the lies escalated to the point of our relationship becoming unsustainable.

Yet life is not a movie, and no matter how many jokes I made with my friends that my life was becoming “just like a movie” as a coping mechanism, the real world and real relationships are more complicated than it’s possible to convey in ninety minutes before the credits roll. Yet what movies are great at doing, one of their best strengths as an artistic medium, is being able to hone in on the essence of a theme or idea in a way that feels truthful to our reality. Movies are focused expressions of human experience, with the edges sanded off and the interludes stripped away, and in that context, Run is one of the few movies I can think of that accurately captures what it felt like to live with my mother from the years of 2017 to 2020.

It’s not a direct analogue. Rather than being in a wheelchair, my disability is invisible; I’m autistic, and struggle with a lot of the daily social interaction that human society expects to be second nature. My mother was not secretly feeding me muscle relaxants to atrophy my legs in order to keep me from going off to college. Yet the essence of my experience, of feeling trapped with someone so changed by grief that they turned around and inflicted that pain upon the only other person in the house, was reflected. I saw myself in Chloe’s attempts to decode the lies her mother tells her, to weather the psychological scars of years of emotional abuse.

Putting words to what I endured took me a long time, but I felt stressed, anxious, depressed, paranoid and defeated on a daily basis because a person I relied on and cared about made my life and her own astronomically difficult. Watching our financial safety net be decimated in a few short years on a whirlwind of indulgences and addictions, with me powerless to do anything about it because of the enforced poverty stipulations of disability support programs, made me feel like my father’s loss was for nothing. That for all his hard work and planning, even in the case of something terrible happening to him, it was all ripped apart anyway, and there’s nothing he could do about it.

When it comes to the physical experience of those years, I remember the sounds most of all. The screams and crying when I refused to hand over cash at ungodly hours of the night, the smashing of mugs and glasses thrown at me in anger that I barely dodged, the shouting matches with a string of lowlife boyfriends who took advantage of her compromised state, the furious banging on the doors from a group of people demanding their money back that she casually told me to ignore. When it comes to my mental state, I remember how my therapist helped me come to articulate those years in as succinct a manner as I likely will ever have:

“I feel I’ve never been allowed to process my own grief because I’m always dealing with hers.”

When Chloe is locked up in the basement after an escape attempt, she learns the truth about her mother: that Diane Sherman isn’t her mother at all, that Diane’s daughter died a couple hours after being born, and Diane stole Chloe from another couple in the maternity ward. It’s a telegraphed twist, one I surmised as early as the prologue, but it establishes an important foundation for the confrontation to come, where Diane pleads her case to Chloe and says “Everything I do, everything is for you, Chloe.” It’s an absurd statement, one that has no basis in the reality of their relationship or anything portrayed in the film so far. Yet it’s also an honest expression of Diane’s reality, because this is the lie that she wholeheartedly believes.

I’ve heard statements like this. The airy tone of voice, the barely held back tears, the deliberate refusal to engage with what the other person is saying, to accept your perception of what you’re doing over what you actually are. It is agonizing to deal with, and yet what makes it doubly so is that it’s so perennially understandable. I would imagine that coming to a place where you’re able to admit that you have been making terrible choices and inflicting untold harm on the people you love for years at a time, to unravel your own emotional and psychological makeup so profoundly, is such a catastrophically unbearable threshold to cross that some people are simply incapable of doing it. Believing the lie is the only way some people can make sense of their existence.

For seventeen years, Diane believed the lie. She believed it with such conviction that she changed Chloe’s family doctor over a dozen times, cut off every other relationship she had, and attempted to destroy her daughter’s chance at a future so she wouldn’t have to give up her charade of a present. Asking her to walk that back, to take accountability for her actions, to understand the magnitude of her sins, is simply too big of an ask. There is no world where Diane Sherman can come to terms with who she became in the vain hope of what she desperately wanted to be.

The mask can crack, but it can never be shattered.

Because eventually, the mask is all there is.

I did eventually leave my home and my mother behind. It took far longer than many would likely expect, but there came a point where every rationalization I had for staying was crushed by the cold reality of our impending deaths. I knew that if I stayed much longer, neither of us would survive. I was barely clinging to what traces of my mental health that remained, and she was using the kinds of drugs you take when you know the end is near. I fled in the middle of the night, not knowing if I’d ever see her again.

I would. Sooner rather than later; only a couple months passed before our next encounter. In fact, me leaving appeared to be the wake up call she needed to finally realize how she had systematically pushed away every good person in her life who cared about her and insulated herself in a bubble of escalating anger and frustration. I bore the brunt of that anger and frustration for years, because I hoped that if I took enough pain on her behalf, that she would eventually work through it and be able to resume a normal life. But suffering is not a prerequisite for a familial relationship, and it took me a long time to accept that.

It has been more than a year since I left home. In that time, my mother’s condition went up and down. She did accept help for her addiction concerns and ejected many toxic people from her life, but later relapsed and was hospitalized for a near-fatal overdose. I was not present for these events, and had to hear about them second-hand. I even had to call the hospital where she was admitted, not knowing at the time if she was alive or dead. We spoke on the phone occasionally, but our relationship felt like little more than a cordial obligation. I didn’t know if it would ever resemble normalcy again. I didn’t know if I wanted it to.

That choice, like so many other things, was taken away from me.

The climax between Diane and Chloe takes place at the hospital, after Chloe intentionally drinks organophosphate in a gambit to force Diane to get her out of the house. Knowing that Chloe will attempt to communicate with the doctors, Diane instigates a patient emergency as a smokescreen to sneak Chloe away. Backed between a flight of stairs and the incoming hospital security, Diane then realizes that Chloe has locked the wheelchair, with her legs regaining a small amount of functionality after weaning off the relaxant Diane had been giving her. Chloe then triumphantly declares “I don’t need you” seconds before Diane is shot and arrested.

As part of the narrative, it’s a fitting rebuttal for Chloe to reverse the power dynamic, “defeat” the antagonist, and finally declare herself free from Diane’s suffocating influence. However, it’s also a very specifically movie-like idea, that such an all-encompassing relationship could be rejected in such an efficient fashion. The movie even acknowledges this with the final scene before the credits, which, while punchy in the same pulpy thriller mode as the rest of the film, does subliminally speak to something more than just an “oh snap” ending: that this kind of a relationship never leaves a person, that it becomes fundamental to who they are going forward.

I know I’ve experienced this, and it worries me. As much as I see myself in Chloe, in her struggle, I have also seen bits and pieces of myself in Diane. I too have a cracked mask, one that splinters in those rare moments where my own anger and frustration reach unsettling boiling points, when I speak about the resentment I feel towards the nebulous forces of the cosmos for making me endure years of pain and turmoil, of perhaps asking a little too much of the people who care for me as some sort of recompense for what I’ve suffered. It’s a side of myself I try to suppress, but to deny it exists is to be as willfully unaware as Diane is.

Part of what’s satisfying about movies is how they can offer tidy resolutions to conflicts that mirror the ones we go through. These are constructed stories after all, and the craving for a definitive ending that validates our worldview is hard to resist. But life isn’t tidy, it doesn’t conform to the pre-packaged scenarios we wish we could enforce upon it, it doesn’t end when the house lights go up. For as much strain as those years put on my mental health and physical well-being, as easy as it would be to slip into vindictiveness and solipsism, even though she derailed my life trajectory in a way I can probably never recover, some small part of me still craved reconciliation. A part of me, in some way, was still dependent on her, on the bond we shared that has a history that goes far beyond our recent tribulations.

Yet that chance at reconciliation ended when my mother was hospitalized a second time. Like my father, I never saw her wake up in the hospital bed. She had overdosed again, and she wouldn’t pull through this time. At 11:20 PM on January 22nd, 2022, my mother joined my father. She was only a couple weeks out from her 48th birthday. Neither of my parents made it to the age of 50. I will never receive an apology for what she did to me. She will never hear all the things I still had left to say, or see all the things I still had left to achieve. The only thing I can be grateful for is that her suffering is over.

In the end, I wasn’t Chloe, stomping my feet down and saying “I don’t need you.” For as long as I can remember, I was Diane, placing her hand on the glass and asking for an answer to an unanswerable question.

“Will she be okay?”

I can only hope.

If you’d like to read more of Carlos’s work, you can find it here!